Recently I was at a Home Depot when a young African American man was helping me with a propane gas purchase. To get to where I was waiting for him, he sprinted like a running back I would have blocked for if we were on the same team (so long ago). Releasing the mental image into the air I said, “someone give that brother a football!” We both laughed. Then, in response he said, “Can I ask you a question?”

In that brief space of time between him asking, and me saying, “sure”, I had that familiar feeling when I believe I’m about to gain new insight. It turned out that the notion was justified. As the conversation unfolded, it got me thinking about belonging, groundedness, and a concept I will describe later, “radical skepticism”.

After getting permission to go beyond a product purchase he asked, “Do you know anyone connected to a local sports team? I’ve been working on my running game and think I have something to offer. I can keep getting hit and get back up.” When you’ve played football, you can often pick out others who have, and it turns out that I was right about him having played–as a running back. He was about 5’8″ and had a football kind of build. In the same moment I thought about whether he could make it as a professional player he then asked, “Do you think I’ll grow anymore?” From there he went on to say that his father was about the same height, but he doesn’t speak to him.

When I responded that I didn’t have those kinds of contacts, he pivoted. “What about anyone with a recording studio? I have some product I think people would want to hear. ” Here again, I didn’t have anything I could offer. Then he finished his thought. “I spent some time in juvenile detention and I’m having a hard time making it. I’ve been here at Home Depot for a few months, but I haven’t advanced.” I didn’t have the kinds of contacts he was looking for, but what I did have right then was the time to offer to him the kind of advice I would offer my own sons had they asked the same questions. “I know you may want more for yourself, but the best thing to do right now is establish yourself with the job you have. Build credibility here, and that will be your foundation for something greater.”

My own father had a way of talking about life that focused on what really mattered. Most importantly, he always listened to my grandiose ideas about what I wanted to pursue and found a way to encourage me. Even though he didn’t make it past third grade and held blue-collar jobs his whole life, his presence added definition to mine. Prioritizing the time to listen made me feel like I belonged to him as his son. It completed the equation that began with my mother’s ambitious expectations. Grounded in those expectations, I had the confidence to reach higher.

When I left Home Depot, with that can of propane gas, I felt that I gave what I could, but perhaps not all that the young man in front of me — seeking connection, encouragement, and advice, needed. This set my mind on fire, thinking about all the other young children who may be adrift simply because they lacked a sense of belonging. It also made me think about Rene Descartes.

Descartes is mostly known in the math world for his system of coordinates (x,y) used primarily in grids and geometry. But in Philosophy, he is credited with that short phrase, “I think, therefore I am.” What’s not typically known is that the phrase marked the end of a long journey he travelled inside his own mind. In his essay, Discourse on the Method (1637), he tumbles down into a pit of doubt once he begins to challenge his own perceptions. Because objects like wax candles changed physical states–or lacked stability he questioned their true nature.

He also questioned his own experiences as he slipped back and forth from dream states to awakened states. He momentarily lost his confidence to identify the difference because he considered the possibility that an “evil demon” was tricking him into believing whether his dreams were reality or vice versa. This growing detachment from the world around him, loss of trust in his senses, and intense questioning of reality itself is what is described as “radical skepticism”.

He experienced these thoughts alone in his cabin. Is this where our children find themselves when rejection or a lack of belonging– alone in a remote cabin? Descartes saved himself when he realized that the only thing that an evil demon couldn’t manufacture was Descartes’ own doubt of his existence. That “doubt” became the “thinking” he refers to in his famous quote. Can our children save themselves in the same manner? Are they fighting their own version of radical skepticism–looking for their own way to establish their own existence, or to trust the world they perceive?

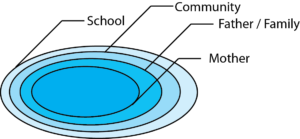

Academia has deep scholarship on the importance of “belonging”. In the “Origins of belonging: social motivation in infants and young children“, a publication of the Royal Society, the author makes that case that a child’s first contexts of learning are based on where they first belong. In the research brief, “What We Know About Belonging“, the author, Carissa Romero writes that students who experience it are “more ready to engage in learning”. One of higher education’s most respected authorities in the realm of student achievement, Vincent Tinto, built a model of student persistence that includes the topic. Finally, Psychology Today asserts in a 2019 article that belonging is a lifelong necessity.

With that moment of shared laughter and a sense that we both belonged to the brotherhood of football, the young man at Home Depot was willing to hear what I had to share about life and potential next steps. Unwittingly, in that relatively brief exchange, I had stumbled into a formula for encouraging learning that’s supported by literature:

1) Acknowledging the student before you as valuable and talented

2) Find an authentic connection through shared experiences

3) Take the time to listen to their aspirations and help ground them in an objective perspective

4) Share a piece of yourself when offering insight

5) Reinforce the fact that your connection is unconditional

Each level of belonging likely requires the same formula. Without it, students likely find themselves skeptical that the world you are painting for them is a world in which they exist.