When one mentions “parents’ advocacy” in November 2021, especially in the context of schools, one likely thinks of the raw conflict currently playing out between parents and school boards around the nation. Those confrontations are distractions. There are more fundamental questions to answer concerning the relationship between the education students of color receive and what their parents expect.

Among fundamental questions to be answered is the source of those expectations. How do we as parents arrive at what to expect? And on what should those expectations be built? A first pass at possible options include: a) what we experienced as children ourselves; b) advice we receive from others; c) what we learn from our own research; or d) what early observation of our children’s abilities reveal. The last option, our child’s abilities, is where this discussion begins.

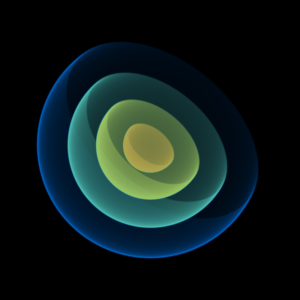

Taking a step even further back, how it is that children go from mystery at birth (in terms of what we know about their abilities) to an emerging student offers many points of divergent thinking. One of the first points of divergence is between those who see children being born “hardwired” with certain abilities versus those who believe a child’s potential is developed at birth. The group that favors hardwiring could be considered “innate ability theorists” or “nativists”. Their beliefs are represented by linguists like Noam Chomsky who believed that children are born with linguistic abilities. More specifically, he believed that all children emerge from the womb with a mechanism in their brains that would use “universal grammar” to begin computing whatever language is spoken by their new environment.

Unfortunately, also among “innate ability theorists” are people like Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, the authors of “The Bell Curve”. That polemic and roundly rebuked 1994 book ascribes differences in intelligence quotients (IQs) and student performance to genetic predisposition. To date, no scientist has been able to tie intelligence to any genetic markers, but the authors’ explicit notions survive.

Those who believe that a child’s development begins at birth could be called, “blank slate theorists” or “empiricists”. Their beliefs are represented by psychologists Claude Steele (covered in a previous post), Joshua Aronson, a research team led by Carol Dweck and quintessential psychologist Jean Piaget.

Steele, Aronson, and Dweck have all contributed to the idea that intelligence is incremental, not fixed. The “growth mindset” attributed to Dweck contends that intelligence is “expandable through effort and experience”. Steele refers to her work in his 2003 article, titled, “Stereotype Threat and Student Achievement” and appearing in the book, “Young, Gifted, and Black”. He writes further that a growth mindset can also diminish the effects of the observed stereotype threat, the phenomenon which sabotages the confidence of students of color with unsound and racially biased expectations of academic performance.

Jean Piaget developed a quintessential theory of cognitive development. His theory tracks the growth of young minds from 0 through various stages:

| Stage Name | Age Range | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor | 0 – (18-24) Months | Infants begin with their use of senses to learn about the world. They also learn that hidden objects still exist (object permanence) |

| Preoperational | 2 – 7 Years | Toddlers and pre-schoolers learn how to represent the world they have engaged with language or symbols. They also use their imaginations to “give life” to inanimate objects |

| Concrete Operational | 7 – 11 Years | Pre- and young adolescents begin to think logically. They can begin converting the shapes of mental images, and are able to consider how other people think. |

| Formal Operational | 12 Years and up | Full adolescents learn how to grapple with abstract ideas. They can also form answers to hypothetical questions. |

Also implied by Piaget’s stages is that idea the child is at the center of development. Learning is solely described from the perspective of the child, rather than the result of interaction with parents or other people. This implication brings forth yet another divergence—between those who prefer to see children develop “naturally”, or based on their interests alone versus those who prefer to “nurture” their children.

The debate over which approach is most responsible for educational outcomes has not concluded. Yet there are strong advocates on either side. In the new Will Smith movie, “King Richard”, Richard Williams (the father of Venus and Serena Williams) is strongly portrayed as a nurturer. However, what the movie also questions is whether his irrepressible desire to nurture his children snuffs out his daughters’ own lights or causes them to burn brighter. King Richard is definitely worth seeing to instigate answers to that question and others posed by this post.

Are the parents seeking to “nurture” their children simply implanting innocent minds with parental ambitions without paying attention to what their children want, or what they are able to do? Can children who are left to their own devices by naturalist or innate ability theorist parents able to reach their potential on their own?

In my previous blog, I ask another series of questions intended to offer approaches to prepare students for calculus by high school. Yet, I recognize that having that kind of ambition might be criticized by “naturalists” for pushing students down a path that such parents might believe the student’s experiences did not destine for them. They might also accuse such parents of putting too heavy a burden on their children (as do those criticizing the so called, “tiger moms”). Innate ability theorists may also push back on the idea of trying to nurture math talent if those students weren’t born with a mechanism like Chomsky’s contemplated (but yet unproven) “universal grammar” translator—naturally able to compute early math concepts.

My wife and I were and continue to be “nurturers”. Unlike King Richard, we didn’t have a full plan to implement once our sons were born. However we considered ourselves to be our sons’ first teachers, reading to them before they could talk, creating opportunities to teach fundamental math at home even while cooking pancakes, and taking them to science oriented events for kids. Learning was fun and ambition was built upon the fact that they seemed eager to learn what we shared. Thus, our advocacy for a great education was built upon the efforts we had invested and the results that were manifested. I cannot prove that they were not born with their early academic potential, but the evidence of early success was revealed as we experienced learning together.

Where do you see yourself? Are you a naturalist or nurturer? Do you subscribe to the innate ability theory or are you convinced by the potential of the growth mindset and Piaget’s cognitive development theory? .

Answering these questions can form the basis of academic expectations. They are also fundamental to building a stance upon which one would advocate. In recognizing our beliefs about how children learn, one can then put one’s own education, advice we get from others, and our research into perspective. From there, we can then bring into focus the kind of education which might be best suited for our children.

There are a lot more questions this month than answers, but parents have to arrive at them on their own. I revealed my own convictions. But my hope is that parents find the healthiest balance between the early time they invest, expectations based on opportunity, the advocacy of an appropriately challenging curricula, and a combination of the developing interests and talents exhibited by the children they raise.