Envision a long wooden table in a Maryland home owner’s back yard covered with a long and clean sheet of brown paper.

Now imagine seeing small wooden mallets spaced about three feet apart where plates might go. Focusing in, you then see two identical containers of spice sitting the middle of the table. What kind of spice is it? What is about to happen? If you have spent even one summer in Maryland, you were likely able to conjure up in your mind two small shakers of Old Bay seasoning, that shall be sprinkled on the blue shell crabs about to hit the table. Your prior experience has prepared you to anticipate what would be appropriate given the setting you observed.

Ideas of “appropriateness” and “anticipation” are emblazoned in the pages of Carter G. Woodson’s landmark book, “The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933)”. His biting commentary concerning the poor state of Black education challenges his contemporaries to focus their remedies on the context in which Black students live.

“And even in the certitude of science or mathematics it has been unfortunate that the approach to the Negro has been borrowed from a “foreign” method. For example, the teaching of arithmetic in the fifth grade in a backward county should mean one thing in the Negro school and a decidedly different thing in the white school. The Negro children, as a rule, come from the homes of tenants who have to migrate annually from plantation to plantation, looking for light which they have never seen. The children from the homes of white planters and merchants live permanently in the midst of calculation, family budgets and the like, which enable them sometimes to learn more by contact than the Negro can acquire in school. Instead of teaching such Negro children less arithmetic, they should be taught much more of it….(Woodson)”

Woodson’s argument to focus advanced training or curricula on the students whose life experiences have offered fewer opportunities for tacit learning would even be unconventional today. The convention in modern education is to make advanced curricula available based either on demonstrated aptitude (usually involving tests) or by lottery. Visit a school system where the median income of its families is high, and you would expect a prevalence of advanced placement courses or an international baccalaureate curriculum. Visit a school district where the median income is low or the families are more diverse, the opposite would be expected.

This pattern bears out in a 2018 study in Connecticut that found only one in 10 low-income students having taken AP courses. The College Board, the author of AP courses itself, also acknowledges equity gaps in course participation.

However, Woodson was not only promoting advanced education in the traditional curricula, but he was also keenly focused on the practicality and applicability of that education.

“What Negroes are now being taught does not bring their minds into harmony with life as they must face it. When a Negro student works his way through college by polishing shoes he does not think of making a special study of the science underlying the production and distribution of leather and its products that he may some day figure in this sphere. The Negro boy sent to college by a mechanic seldom dreams of learning mechanical engineering to build upon the foundation his father has laid, that in years to come he may figure as a contractor or a consulting engineer. (Woodson)”

In this section of the book he also reflects on his own education by comparing his fate — “begging for a struggling cause”, which he ties to his undergraduate focus on sociology and philosophy, with the independent wealth of his colleague who studied “wool” in order to build a business. In essence, he challenges the reader to consider the value of a liberal arts education. In an earlier post I argued that the value was intellectual and civic in nature. By holding up that well noted essay by William Cronin, I now find myself challenged as well to consider whether those beliefs would leave Black children under-prepared for the world that specifically awaits them.

To begin taking on Woodson’s challenge I reached out to the owners of a new cafe in Bowie, Maryland called, PJs Coffee of New Orleans. Having opened in 2020, during a pandemic, their success bucks the retail narrative over the last few years. This African American power couple directed their experience in the corporate landscape of mergers and intellectual property toward building a franchised business. Together they reflect exactly the kind of ideal for which Woodson committed his thoughts to paper. How did their education and their background prepare them for success?

After setting things up at their cafe, Michael and Tyra Harris shared their story with me via Google Meet. “The idea for the cafe really came from an appreciation for good coffee and having to drive into DC to find it,” Mrs. Harris began. “We identified a void and decided to fill it”. Initially they contemplated building their own coffee brand. But after Mr. Harris researched what needed to be known regarding supply chains, overcoming market forces, and opportunities for growth they decided that finding a franchise would be a more feasible path.

With a franchise, they could tap into a corporation’s buying power, bargaining position with suppliers, and established brand. Next they had to figure out which franchise would meet their standards.

On an unrelated business trip to New Orleans, a city that they both love, Michael just so happened to walk into a PJs Cafe there. Having tried the coffee black–he reveled in the authentic taste. Then having tried other flavors, it was time to call Tyra, “I think we have found the franchise!”. So along with Tyra’s mother, the three of them convened in New Orleans and visited the cafe together. What stood out in the subsequent visit was the hospitality–an immediate greeting upon entry and the feeling that you were more than just a customer.

With more research they found that they could also get behind the corporation itself. They discovered that the founder was a woman. “PJ” is “Phyllis Jordan”, who in 1978 who brought new ideas regarding bean cultivation and coffee roasting to the industry. They were also compelled by the chief coffee roaster, who is African American, and who made himself accessible to the Harrises while questions regarding the roasting process flowed.

Their vision was now complete. They would sell high quality coffee through an established franchise and create an environment where people experience southern hospitality. Once all of that was in place, the next phase was opening. Originally planning to open in February of 2020 they had to delay the opening six months. The delay set them against accumulating leasing bills but they made good use of time by building up expectations in social media.

They finally opened in August of 2020. I was there during that first week and witnessed the pent-up energy they had been cultivating. People were buzzing inside and outside of the café. As of the writing of this blog, eight months later, the energy persists. On any given day you will see customers chatting, sipping, or eating.

“Accounting?”, “Biochemistry”? When finally putting the question to them about formal education they found to be relevant to their success, Mrs. Harris said that the only course she could think of was accounting. As the company’s chief financial officer the connection is of course apt. Michael was a Biochemistry major and said it’s possible that his disciplinary training prepared his mind to break down large concepts into smaller ones. He added that his current ability to solve problems was aided by the study habits he has maintained years after college. As evidence he referred back to the research he completed to understand how the coffee industry operates and how to find PJ’s place within it.

So far, it sounded like the education that they would consider to be relevant was adapted as opposed to having been taken intentionally. Neither went to college with a specific idea of a business they wanted to build. Had Woodson been asking the questions today, he may have wanted to see them receive more preparation to make a living. Yet, they have picked out skills they acquired then in order to implement them now.

The most compelling aspect of their background, however, comes from their extended families. Both of their families are from further South, Alabama and South Carolina. In both of the counties where their relatives thrived Michael noted that, “people were groomed to own their own businesses.” Both Michael and Tyra’s earliest memories of life in the South, were of Black doctors, lawyers, grocery store owners, property owners and other entrepreneurs–though they had to wade in the murky waters of segregation. This part of history raises the question of whether the pursuit of industrial opportunity “Up North” was worth sacrificing the entrepreneurial opportunity that remained “Down South”. I’ll save that question for another time.

Clearly the Harrises’ early exposure to successful entrepreneurs helped them recognize how a table might be set in order to realize future success. That kind of mindset goes beyond the typical go-to-college–get-a-job–retire pattern that’s so familiar to most of us. Instead, they are converting their jobs to ownership like their relatives before them. They also hope to transfer this mindset to the young baristas who now work for them. In doing so, the Harrises shall be correcting the “mis-education” that the younger generation may have also received.

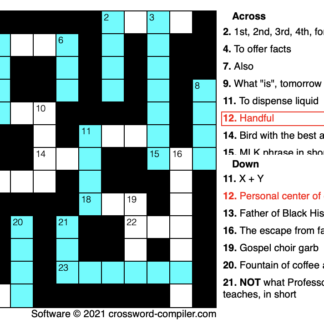

As an early response to Woodson’s challenge then, and based on the Harrises’ experiences, an appropriate, practical, and appropriate education could include:

1) Helping students identify connections between their experiences and the kind of knowledge they could acquire to move from consumers to producers or from buyers to owners;

2) Teaching students how to adapt cognitive and academic skills when encountering unanticipated opportunities;

3) Exposing students early to successful ways of living, which includes ownership, while showing them how to compare lifestyles between owners and employees; and

4) Giving students the tools to recognize when their thinking is holding them down–drifting on a negative trajectory–or when their ambitions are too small relative to the potential they possess.

“The so-called modern education, with all its defects, however, does others so much more good than it does the Negro, because it has been worked out in conformity to the needs of those who have enslaved and oppressed weaker peoples. …No systemic effort toward change has been possible, for, taught the same economics, history, philosophy, literature, and religion which have established the present code of morals, the Negro’s mind has been brought under the control of his oppressor. The problem of holding the Negro down, therefore, is easily solved. When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. …You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. (Woodson)”

Except for the anachronistic use of “Negro” throughout, I contend that it would be very difficult for those unfamiliar with the author’s life to put a publication year on this book. It’s relevance to modern educational philosophy and outcomes is stunning. This author greatly appreciates the challenge from that author as I too like philosophy, and have similarly discovered that there are a great many thoughts that are non-fungible. Thus, my views of what should constitute “high achievement” shall be adapted to honor his legacy.