Defining achievement for students of color within the context of 2021 should be much different than it was for the free and enslaved students at the recently rediscovered Williamsburg Bray School in 1760.

Yet, the historic record of what was likely to be the first school in the nation founded to educate Black students is revelatory. That record opens a narrative showing how for more than 260 years and counting, ambitious Black families seeking excellence have had to settle for the educational equivalent of “hog maws”.

It’s true that families hailing from the south have figured out how to clean, season, cook, and eat hog maws and chitlins. I know this from personal experience as my family originates from South Carolina and ate them around me. I know what they look like in the pot and how they make a house smell while they are being cleaned. What’s also true is that the prevalence of this “delicacy” reflected our plantation heritage where slaves received only the “undesirable parts” of the animals after the planters ate first. Stated differently, we had to make the most of what was socially acceptable for our station and wait our turn.

According to a February 25th article in the Washington Post, The Williamsburg Bray School was founded in 1760 to educate Black students. While the effort on its face seemed noble, their mission was suppression. In the way that they converted students to Christianity they intended on inculcating the notion that their lives at the bottom of the social order was mandated by God. However, in the same manner that the cooks of discarded pork created something valuable with it, the Post article suggests that the students used their education to build their powers of literacy and resist subjugation–at least psychologically. Perhaps all that could have been expected with regard to achievement in their cases was a free mind.

In the context of colonial Williamsburg, VA between 1760 and 1774, one could also argue that simply getting any education at all constituted achievement. The prevailing societal imperative was to preserve slavery and white supremacy at any cost. Or, one could consider the ability of a few literate Blacks during that time to forge interstate travel passes to freedom symbolically significant.

One such person, Isaac Bee, was considered a notable “scholar” and alumnus of the school. Ironic for someone considered a scholar, he was also a slave that became a fugitive. Based on an ad seeking his retrieval it was believed that he might use his literacy to forge a pass, but his story ends with him still showing up on tax records, having been returned to the possession of his “owner”.

A more well known and close contemporary to the Bray School was the New York African Free School. Founded in 1787, its mission was not as overtly religious or intentionally pedestrian in its curricula. On the other hand, according to historian John Rury, the school sought as its main mission to “divert Black children from the slippery path of ‘vice'”. That’s also not a high bar for achievement.

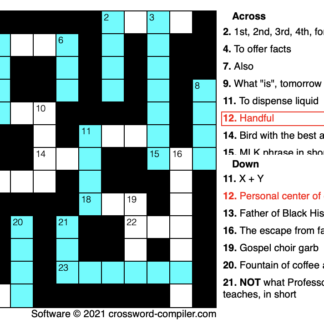

They employed an efficient, but mechanical method of teaching. Known then as the “Lancastrian” system of education, the system involved teaching the newest lesson to the most adept students first, and then dispatching them to teach that lesson to the rest of the class. The trade-off was that while more students could be taught at a lower cost, there was almost no room for intellectual exchange with instructors. Thus, they were learning facts, but not thought processes.

Yet, unlike the Bray school, the African Free School does record some individual successes. Alumnus Ira Aldridge attended the school around 1820 and became one of the most celebrated Black actors of the 1800s. James McCune Smith graduated in the late 1820s and became the first African American to earn a medical degree. However, the achievement of a few should be considered insufficient given that so many Black parents from that day had engaged the school and had much higher educational aspirations for their children.

Fast forwarding back to 2021 we can still ask questions about education quality and opportunities for high achievement. When the parents of students of color assess their educational options, many will find themselves having to settle for “less than”. While we don’t see the same open hostility to the simple prospect of getting an education, the idea of equalizing opportunity for high value education still sparks controversy. In a future post, I will look at what luminaries of Black education have written in response to historical roadblocks. I will also point to specific approaches that have been suggested to overcome them.