(academic version)

Given two turntables, a sound mixer, and a stack of records from the eighties,

could you find two songs that are close enough in beats per minute and blend them together? What if I could demonstrate that the ability to synchronize two different records reflects the deeper intelligence required to reconcile one’s existence between two separate worlds?

Moreover, what if I could prove to you that this kind of intelligence is critical to African American success? Such an invention would escape the measurement of any modern standardized test, but doesn’t rule out the possibility of its existence.

What exactly is “intelligence”? Generally foregoing a dictionary, we think of intelligence as that which is determined by Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon’s “IQ” test. The precursor of the test was introduced in 1906 with a paper authored by Binet and Simon. Their purpose back then was to classify populations of children based on degrees of ability–stretching from the apt to those with more limited functionality.

What exactly is “intelligence”? Generally foregoing a dictionary, we think of intelligence as that which is determined by Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon’s “IQ” test. The precursor of the test was introduced in 1906 with a paper authored by Binet and Simon. Their purpose back then was to classify populations of children based on degrees of ability–stretching from the apt to those with more limited functionality.

From 1906 through the several iterations that lead to the latest version (SB5), released in 2003, the test purports to measure five factors: (Factual) Knowledge; Fluid Reasoning; Visual-Spacial Reasoning; Quantitative Reasoning; and Working Memory. These factors have been grouped into a single variable called, “g”, which stands for general intelligence. Thus, Binet & Simon would define intelligence as an ability to exhibit those factors.

Yet, their definition is sandwiched by at least 500 years of history preceding it and many scholars who questioned their definition after it was first released. The English form of the word “intelligence” first appeared in 1390. Before the English form, the Latin derivation of the word combines the ideas of “picking out” and “between” to mean an ability to understand differences between concepts.

Also predating IQ tests is a surge of at least western philosophers that probed the contours of “knowledge” while using “intelligence” as the method of knowledge acquisition. Perhaps most notably, Immanuel Kant based his declaration that “The Age of Enlightenment” had begun on the premise that people had gained the “courage to use their own intelligence.” Within this context, Kant is defining intelligence as the ability to contemplate the world independently of how others have defined it.

Among the many scholars who have subsequently challenged the narrow, five factor focus still serving as the basis of so-called general intelligence are Howard Gardner and Robert Sternberg. Gardner published the 1983 landmark book, “Frames of Mind“, in which he argued that there were many more forms of intelligence that one should consider when assessing learning potential.

The eight intelligences he picked out include:

1 – Linguistic

2 – Logical-Mathematical (closest to general Binet & Simon’s general intelligence)

3 – Musical

4 – Spatial

5 – Bodily-Kinesthetic (ability control one’s body and utilize it to solve problems)

6 – Inter-personal (strong awareness of others, and capable of empathy)

7 – Intra-personal (strong awareness of one’s self and one’s abilities)

8 – Naturalist (knowledge of nature)

Over the past thirty-seven years Gardner has continued to develop the theory of multiple intelligences so that school districts and other learning institutions could apply it. The impact of his theory has been broad and substantial. It has given teachers more cognitive tools to contemplate the potential of ethnically and intellectually diverse students.

However, Sternberg, whose views appealed to me even more, and also brought me back to my first question, wrote a paper in 1999 titled, “The Theory of Successful Intelligence”. He, like Gardner, believes that the general intelligence theory is too narrow. But he goes further than Garner to explicitly call out the cultural narrowness of the theory. By creating the term, “successful intelligence”, he is picking out the salience of abilities one develops that lead to achievement in the context in which they find themselves. In his research he finds children in various parts of the world who develop “intelligence” that befits their cultural context, but is unlikely to be measured by the five factors of a standard IQ test.

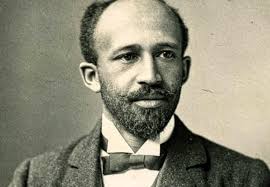

W.E.B. DuBois, renowned scholar and the author of The Souls of Black Folk (1903) recognized the impact of contexts, and the need for African Americans to learn how to adapt to them. He wrote,

“The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with a second sight in the American world,–a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amusement and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, –an American, a Negro, two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

While Sternberg’s theory speaks to the kind of intelligence that includes cultural contexts, the depth of DuBois’ still-present double-consciousness calls out for more consideration. I contend that a term like “Synchronistic Intelligence” may serve that purpose. The intent is for it to describe the ability to go back and forth between worlds, achieving success in each, keeping each going at the right pace, while maintaining one’s identity and soul during transitions. What do you think?

In future blogs I will explore demonstrations of synchronistic intelligence, and why that term explains concepts not captured by newer formations such as cultural or emotional intelligence.

- Sources:

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition

Assessment Service Bulletin Number 1

History of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales:

Content and Psychometrics

Kirk A. Becker - The Theory of Multiple Intelligence, Robert Sternberg

Multiple Intelligence Institute, MI Theory, the Basics, 2008 - Cultural Intelligence: https://hbr.org/2004/10/cultural-intelligence