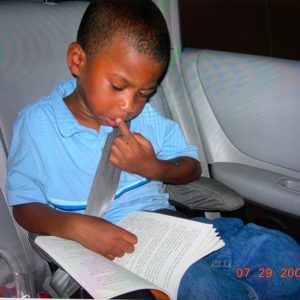

In response to the previous blog, what if you have been using digital devices (whether they are playing action or learning games) to keep your child occupied and now want to know your child’s reading level?

Should your reading level results inform your views on screen time?

To prepare an answer to this question I first considered scientific or research-based suggestions. My intention was to focus on the use of Lexile scores. These scores were created to provide a standard for determining the reading level of the books available to our children. By also obtaining a Lexile score for your child, you could gain more insight into the books they should be able to read, how they compare with others in their grade, and where they might need help. According to their literature, many schools will have found the Lexile score for your child and would be able to share it with you (if they haven’t already).

What is your child’s relationship with the books available to them?

The framework developed by the creators of the score is comprehensive and may be helpful to a parent who wants to stay informed about their child’s reading progress. However, the tactics involved with reading assessment invite controversy. In a paper presented to the 2018 American Library Association two researchers, Lu Benke and Jim Erekson argue that assigning books to students based on a match between the Lexile scores may miss the mark. They found that the interest level of a student in the books presented to them can influence their comprehension. They also noted that different methods of assessing book reading levels (besides Lexile scores) resulted in different conclusions about the same book’s reading difficulty.

In the rest of their presentation, they offer ways to help librarians choose better books for children, but what emerges from their suggested methods is a new theme–that knowing each child as an individual reader improves our insight into their true reading level. Restated, Benke and Erekson are saying that knowing the book a child is reading is not enough; one should also know the child reading the book.

Their advice squares with a conversation I had with a children’s librarian in DC. Julie was a former teacher and had many stories to tell about the families she has seen come together to visit the library. Her advice about assessing reading levels also emphasizes knowing “the reader” or your child, better. Elaborating, she said, “getting to know them as readers involves asking a series of questions about what they have just read.” Such questions could include: What happened in the story? Did you like how it ended? What do you think would happen if there was a new chapter? Did you see they used this word (______) in the story? Do you know what it means?

What Julie suggests is that “assessment” can potentially be more effective when using conversation as the tool to answer the larger question about phone use, rather than a diagnostic test. If your questions about the books they are reading lead to engaging conversations, then perhaps it’s more likely that the times they are using phones to be kept busy are not taking away from their reading development.

Conversely, if your children persistently meet any two of these criteria:

1) they refuse to use physical books to find answers to open questions;

2) they can never seem to find stories in books that pique their interest;

3) they lack understanding of the ideas expressed by the books they seemed to have been reading;

4) the stories they read seem not to provoke any of their own questions; or

5) they only find digital environments engaging;

then perhaps that information is more telling than what you would get from their assessed reading level.

Finding and keeping track of your child’s assessed reading levels in school may be instructive, but those tests are snapshots in time and may not be telling the whole story. By talking with our children often about what they are reading, letting them see us read, and observing their relationship with books overall, we will understand better how to view the time they spend on our (or their) phones.

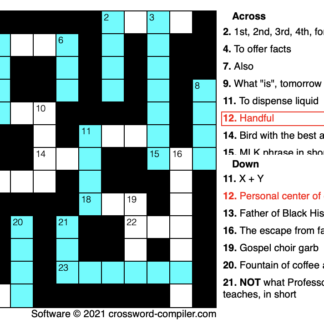

20

Rough number of minutes per day

that children should read*

Finally, here are more resources to consider:

– Reading milestones by age (your own school may have accelerated or elongated versions of these milestones. Just use these as reference)

– A narrative form of reading milestones, but by reading development stage (again, use as reference- each child may have their own starting point)

– *Article suggesting how 20 minutes a day of reading can bolster academic development

– How five kindergarten books a day can potentially propel your child onto the plus side of the achievement gap